Paylaş

After the September 12 coup, a mother goes to visit her imprisoned son. Throughout the journey, her other son teaches her a single sentence to memorize. The mother repeats that sentence over and over during the trip. When she sees her son, she must say nothing else — because her language is forbidden. In this land, just as there is no Kurd, there is no Kurdish language either; it is banned. Of course, we don’t expect the state to know our existence better than we do (!)

When the mother finally sees her son, she says the sentence she memorized. Her son replies — and then asks her a question. But the mother simply repeats the memorized phrase:

“Kamber Ateş, how are you?”

When I think of language, the first thing that comes to mind is the torture inflicted on İpek Ateş. (May the place where you rest never cause you pain).

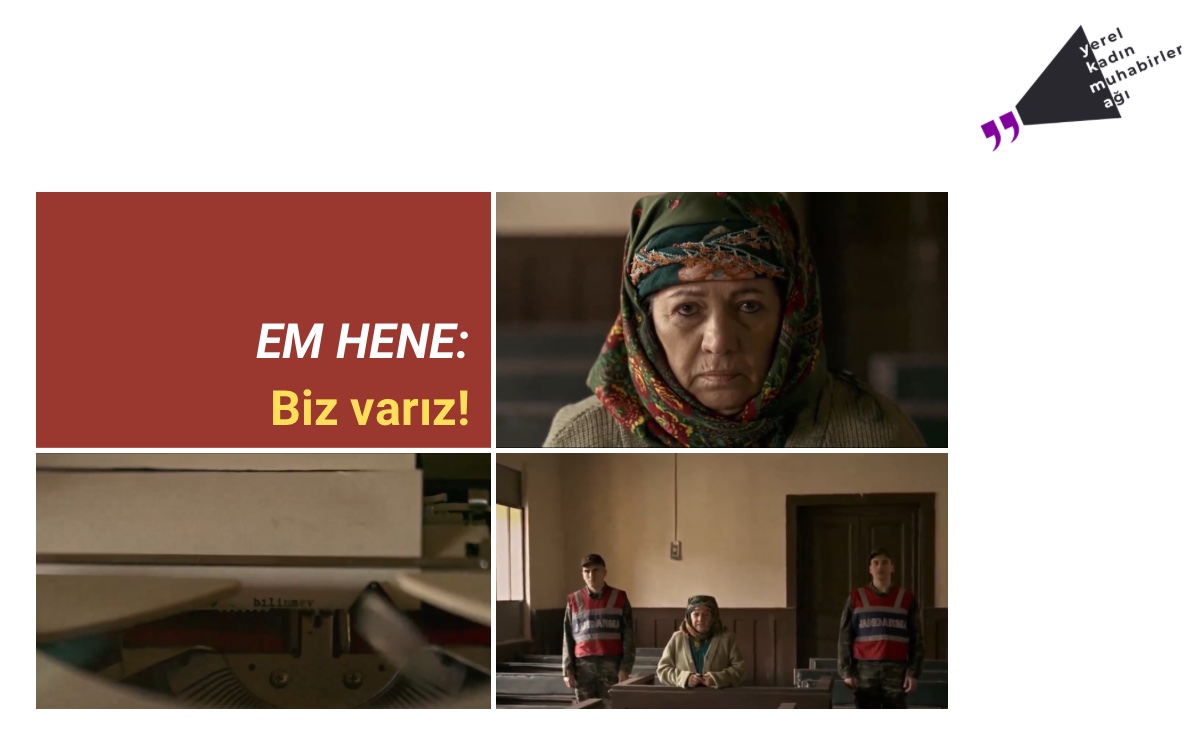

In recent weeks, a scene from the series Şahsiyet, which I also follow as a viewer, was circulating on social media. Yes — the courtroom scene, and the use of Kurdish being recorded as “unknown.” Kurdish is a language. It is the language of the Kurdish people, whose existence is not subject to anyone’s monopoly. Never mind that when elected members of parliament speak Kurdish, it’s marked as “x” in official records, or referred to as “an unknown language” in courtrooms — Kurdish is a known language.

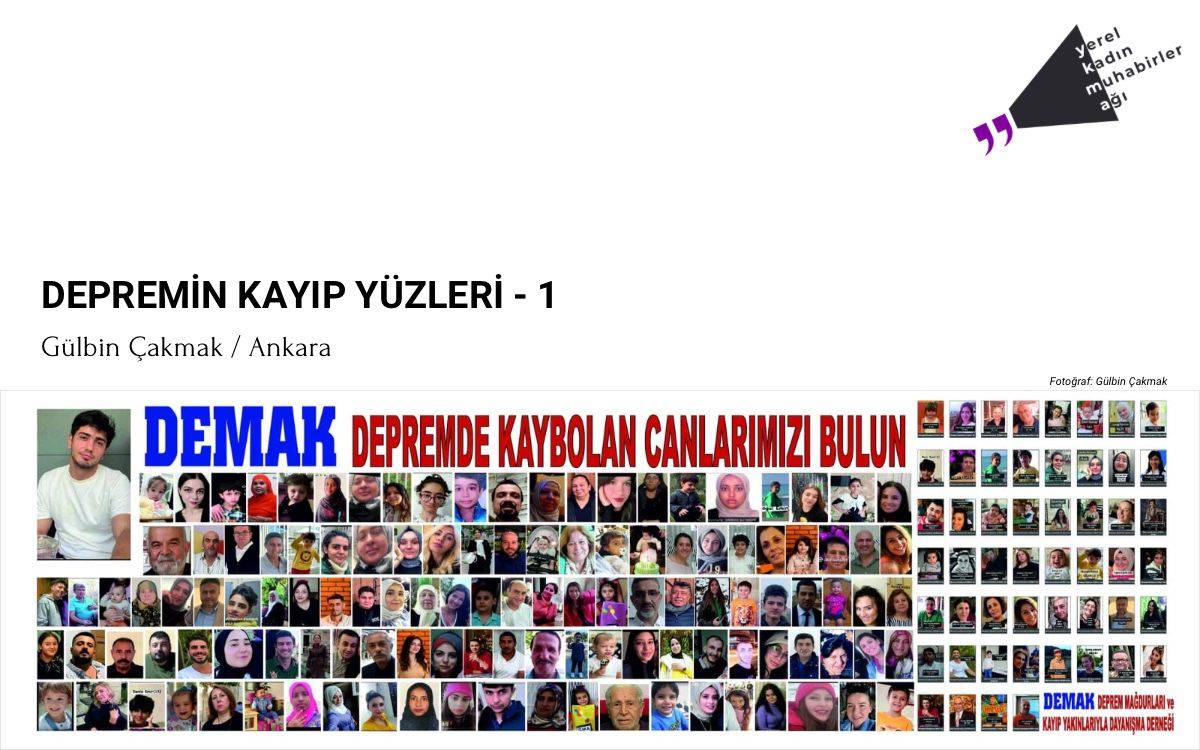

Denying this language, registering it as “unknown,” is no different from erasing nearly twenty million people who only seem to be remembered around election time.

Are we still at this point?

I felt angry while watching the scene from the series that was circulating online. And yet, the show touched on a harsh reality of this region — didn’t it? From that perspective, yes, it served as a reminder. A reminder to a people whose collective memory is, in many cases, worryingly short — especially in the aftermath of an election period driven by nationalism, and despite everything they’ve been made to endure, still choose to stand in the same place.

But there’s also a people in this country with a sharp memory.

For people like me, the scene felt superficial — it didn’t go deep. It was emotionally manipulative, forced, even though the actress spoke Kurdish fluently. The repeated use of the clichéd phrase “an unknown language” felt tired and hollow.

When I asked Selim Temo for his opinion on the matter, he said,

“Let the Kurd be the victim, then a virtuous Turk appears and feels sorry for them—the conscience of Turkish society is eased, and the Kurd is left thinking, ‘They felt sorry for me,’ and somehow feels happy about it.”

Reha Ruhavioğlu, meanwhile, noted:

“It’s as if Turkish society is suffering from amnesia when it comes to the Kurdish issue—behaving as though only the last three to five years of history exist. That’s why, in a time when nationalism is gaining strength, it’s important that a scene like this was even portrayed.” It felt like an “Introduction to the Kurdish Issue” course. But cinematically, it wasn’t a strong scene. There was no imagery — it was shot in a very plain, straightforward way. Then again, in a context where everything has fallen below average, it’s hard to criticize a scene for delivering its message so directly. In the end, it came across more like a public service announcement than a dramatic moment.

During a period when Kurdish rights were under pressure, such a scene was welcomed positively by most Kurds. However, reactions such as “Are we still at this point?” were voiced more loudly among the elite. The elite, who are generally more interested in politics, believe that significant progress has been made and that remaining at this stage is exhausting. However, for the general public, this scene had a predominantly positive impact. I call this the gap between the elite and public opinion.

There were two things that made me angry. First, to some people, we are not even human — it’s as if we don’t exist. To them, we’re objects. We’re treated like forgotten keychains or glasses left behind somewhere. Then someone else comes along and “finds” us, and reminds others — within the limits of their reach — that we exist. For a brief moment, we capture the attention of those within that boundary. And then? Then nothing. We’re forgotten again. Someone rediscovers us, reminds others, and then we’re forgotten once more. It’s a painful, infuriating cycle — one that wears us down.

Isn’t your native language the same as ours?

Today I came across a video where Erdoğan says, “Our greatest weapon against assimilation is to teach our children—the guarantee of our future—their mother tongue, their culture, and the values of their civilization.”

This is a statement I fully support, from beginning to end.

But then I ask—why are you so against Kurds resisting assimilation, while you defend Turks doing the same?

My culture would only add richness and color to yours—so why are you opposed to it?

Öfkeme sebep olan ikinci kısım videoyu dolaşıma koyup beğenisini dile getiren Kürtler’e. Elbette hepimiz aynı şeyi düşünmek, hissetmek zorunda değiliz. Sizlerden ricam size ait olanı lûtfeder gibi sunduklarında bu kadar memnun olmayın. Anadilimiz var ama konuşamıyoruz, birileri dile getiriyor hemen sahipleniyorsunuz. Sahiplenmeniz gereken hakkınız olan diye düşünüyorum. Diziyi izlerken yaşadıklarımıza üzülen ama ertesi gün unutan siz sevgili Türk arkadaşlarım size de bir çift sözüm var: “Görmezden gelmeyi terk etmediğiniz sürece” sizler de sadece bir film veya dizide belki bir kitapta denk geldikçe bizlere üzülüp acıyacaksınız. Sizden beklediğimiz şey bize acımanız değil, bizi anlamanız. Görmezden gelmeyi terk etmeniz. Çünkü hemhâl olmak, hemfikir olmaktan daha iyidir.

Gülbin Çakmak